ID Review: Instructional Analysis

Suggested Readings

Chapter 3, Conducting a Goal Analysis, from Dick, Carey and Carey.

Background Information

Once you have a

description of your learning need and an appropriate, feasible, and clearly

stated instructional goal, the next step in the instructional design process

is to develop an Instructional Analysis. According to Dick, Carey and Carey,

"An instructional analysis is a set of procedures that, when applied to

an instructional goal, results in the identification of the relevant steps

for performing a goal and the subordinate skills required for a student to

achieve the goal" (pg. 38). Dick, Carey and Carey break the instructional

analysis step into two parts: Goal Analysis and Subordinate Skills Analysis,

with each one covered in a separate chapter of their book. Goal

Analysis involves identifying and sequencing the major steps and substeps

required to perform your goal. Subordinate Skills

Analysis involves identifying the subordinate skills and entry behaviors

needed to perform each of the major steps you identify.

Let's look closer at what's involved in each part of the Instructional Analysis:

Goal Analysis

The goal analysis involves describing, in

step-by-step fashion, what a person would be doing while performing the

goal. In order to perform a goal analysis it is important that the designer

possess enough information of the subject matter that he/she be able to

describe what learners would be doing if they were demonstrating that they

could perform the goal. Instructional designers are generally not subject

matter experts in all areas, so you may occasionally need to seek outside

help from an expert (or SME). Once you

have the required knowledge of the subject matter, it's best to start by

asking yourself the following question:

"What exactly would learners be doing if they were demonstrating that they could already perform the goal?"

From this question, you should go through and

list the steps that you would perform if you were attempting to achieve the

goal. This can simply be done in bulleted or outline form. Try to list all

of the steps that are important, and keep in mind that if you are an expert

the steps may seem more obvious to you than they will to others. At this

point it's better to have too many steps than not enough. In addition, if

the sequence of steps is important, make sure that you have identified the

proper sequence. As an example, let's look at the example of changing a flat

tire. Here's a list of steps that might be important when changing a tire:

Assuming you are already parked on the side of the road:

- Turn on Hazard lights.

- Remove spare tire, jack, and lug wrench.

- If necessary, remove the hubcap from the flat tire.

- Using the lug wrench, loosen the lug nuts on the flat tire.

- Jack up the car.

- Finish removing the lug nuts.

- Remove the flat tire.

- Put on the new tire.

- etc.

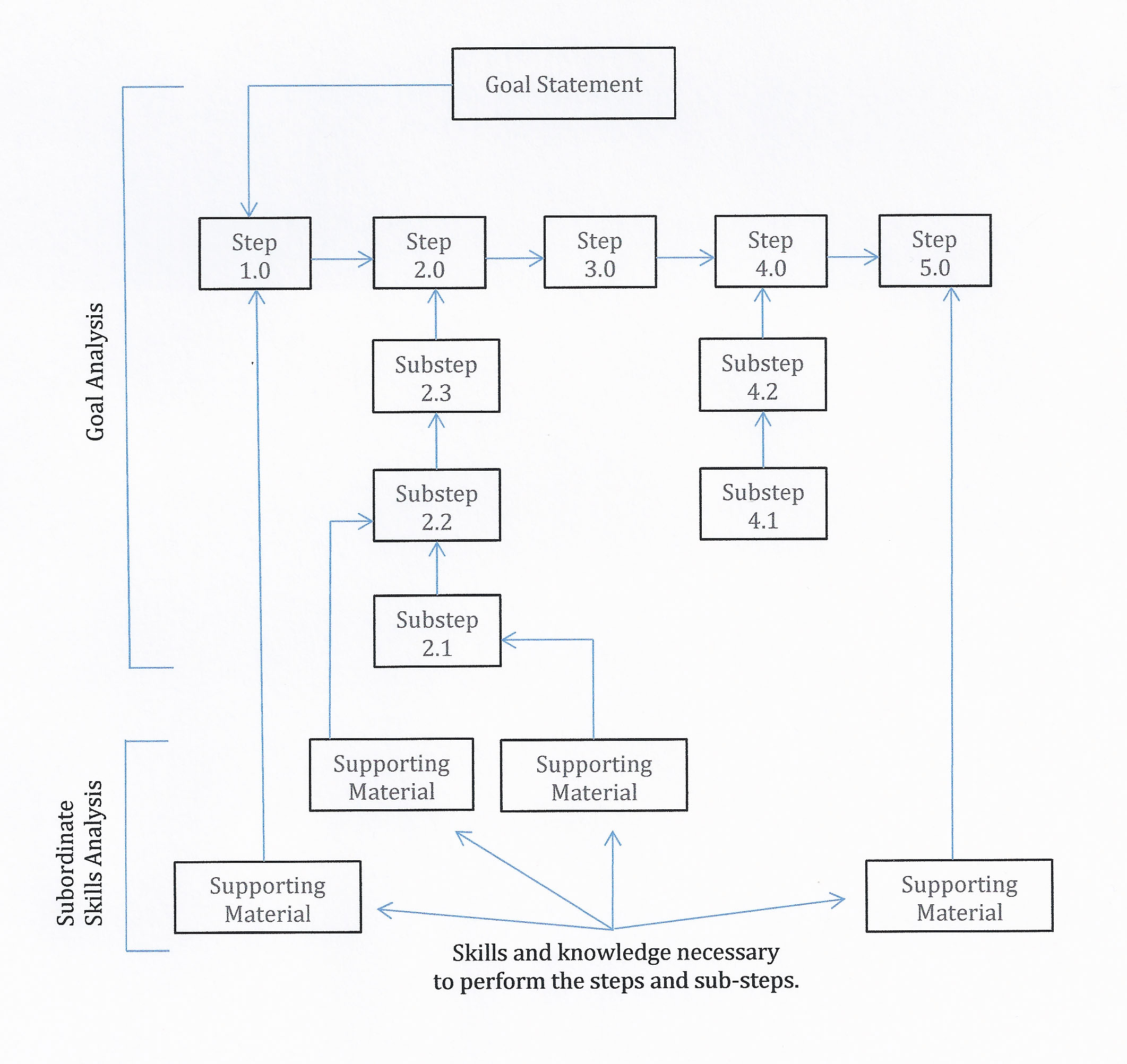

Once you have the goal steps and the sequencing down on paper, the next step is to create a flowchart that presents this information. The use of a flowchart allows you to present the content and the sequence in a way that shows the relationship between the various steps in the process. As you create the flowchart, you should include each of the steps and indicate the behavior being performed at each step. Each step should have an observable outcome. In addition, they should be sequenced in the most efficient order. If there are decisions to be made along the way, include decision steps to indicate that there is more than one possible path. Often the goal is put in a box at the top of the flowchart (see below).

Note that with verbal information there may not be any specific sequence inherent in the information. In other words, it may not involve going from one step to the next. In this case you would not need to connect the boxes in your goal analysis; your flowchart would merely indicate the information that must be covered (see below).

If you have an attitudinal goal, then it is necessary to identify the behavior that you will look for to determine if the attitude is being demonstrated. What would people be doing if they were demonstrating that they were following the desired attitude? This is done by attaching this behavior to the attitudinal goal at the top of your flowchart, and then listing the steps from there (see below).

Substeps

Once you have the main steps written down, you should examine each of them to determine if there are any substeps required in performing a particular step. Certain steps may require substeps. Think about the complexity of each step for the identified learners to determine if substeps are needed. Is it a single process or one that requires several steps? If a step is too large then it may be best to divide it into several simpler steps as opposed to substeps.

On the flowchart, substeps are indicated in boxes that drop below the main step. Notice that the arrows on the lines connecting the main step to the substeps point away from the main step and toward the substeps.

Returning to our flat tire example, lets look at some potential substeps for step 5:

- Turn on Hazard lights.

- Remove spare tire, jack, and lug wrench.

- If necessary, remove the hubcap from the flat tire.

- Using the lug wrench, loosen the lug nuts on the flat tire.

- Jack up the car.

- Substep 1: Insert the jack handle into the socket on the jack body, and turn the handle to raise.

- Substep 2: Raise jack until it contacts the frame of the car.

- Substep 3: Once the jack is raised enough to touch the car, position it in the proper place beneath the frame.

- Substep 4: Raise the car until the tire is about 6 inches off the ground.

- Finish removing the lug nuts.

- Remove the flat tire.

- Put on the new tire.

- etc.

The final product of the goal analysis is a diagram of skills, which provides an overview of what learners will be doing when they perform the instructional goal. This framework is the foundation for the Subordinate Skills Analysis.

Subordinate Skills Analysis

The second part of the Instructional Analysis is the Subordinate Skills Analysis. This involves identifying the subordinate skills and entry behaviors needed to perform the instructional goal. Doing this allows you to decide which skills you are going to teach and which ones learners will have to already possess before they are exposed to the instruction.

The subordinate skills analysis involves analyzing each of your goal steps and substeps to determine what prerequisite skills or knowledge are required to be able to adequately perform that step. These skills and knowledge are referred to as Subordinate Skills. This is different from what you did in the first part of the Instructional Analysis, in which you determined the main steps necessary to achieve your goal. In other words, the steps and substeps identified during the Goal Analysis are the activities that an expert or skilled person would describe as the steps in achieving the goal. The subordinate skills are not steps or substeps on the way to the goal; they are the supporting information that learners need to be able to perform those steps (see below). They would not necessarily be described by an expert when describing the process. The following chart helps explain the concept. Notice the upward arrows leading away from the subordinate skills, indicating that these skills are supporting the various goal steps and substeps.

For example, in order to create a document in Word you would need to open the program, type some text, cut and paste, save the document, etc. In order to do all of that you would need to first be able to operate a keyboard and mouse. Knowing how to operate a keyboard and mouse are not really substeps in creating a Word document, they are subordinate skills that are required in order to perform the steps of opening the program, typing text, highlighting text, etc.

Why is it important to identify these subordinate skills if they are not part of the main steps towards achieving the goal? Well, before performing an activity (step), the learners must (1) know how to perform the activity, and (2) possess the skills to perform the activity. The learners are likely to possess some of the necessary knowledge and/or skills, but will need instruction to acquire the remaining knowledge and skills. Without a complete inventory of relevant knowledge and skills, important instructional components could be overlooked and omitted.

There are several different approaches one can take when performing a subordinate skills analysis. The decision to use a particular procedure usually rests on the type of goal being addressed. For intellectual or psychomotor goals you will likely use a hierarchical analysis. For verbal goals a cluster analysis is recommended. Finally, for attitudinal goals a combination of approaches is used. We'll summarize the various approaches to the subordinate skills analysis in the following paragraphs.

Hierarchical approach

The hierarchical approach, as pictured in figures 4.1 - 4.4 in the Dick, Carey and Carey book, is used to analyze the individual steps in the analysis of goals involving intellectual or psychomotor skills. At this point you want to focus on one goal step at a time, starting with the first one. Look at each goal step and think about what skills and knowledge a learner must possess to be able to perform that step. Gagn? suggests beginning with the question, "What must the student already know so that, with a minimum amount of instruction, this task can be learned?" The answer will likely be one or more subordinate skills. These subordinate skills are what the learners will need to know to be able to perform that step. It may be best at first to write them down in bulleted or outline form, much like you did when you were first identifying your original goal steps.

After you have identified the initial subordinate skills for a step, you should then examine each of those subordinate skills and determine if there are any additional skills or knowledge that the learners must possess in order to learn those skills. This will result in the identification of additional subordinate skills. This process should continue until you reach the very basic level of performance, such as "identifying nouns and verbs". This does not mean that you will have to teach these skills to the learners. Eventually you will determine which of these skills should be classified as Entry Behaviors and not be taught. But for right now, you should include all the relevant subordinate skills. After you have finished analyzing your first goal step, continue on this way, analyzing each succeeding goal step to identify subordinate skills, and then analyzing those subordinate skills to identify more subordinate skills. In this way you will be building a hierarchy of skills that are required to attain each main goal step.

When you think you have identified all of the relevant subordinate skills (subskills) for each goal step, you will want to add these to your instructional analysis diagram. Each subordinate skill should be represented by its own box, and should be connected to the goal step it supports. In addition, it should state the skill that the learner must be able to do at that step. Also, notice that the arrows on the lines connecting each subordinate skill box to the steps and skills above it point up from the subordinate skill towards the higher skills. In a hierarchical analysis, it is traditional to place superordinate skills above the skills upon which they are dependant in order for the reader to automatically recognize the implied learning relationship of the subskills. This means that the lower-order skills will end up at the bottom. When working with these skills, it may be useful to work your way up from the bottom, starting with very basic or foundational skills and then working your way up to the skills most closely connected to the goal step they support.

If your intellectual or psychomotor goal has subordinate skills that involve verbal information, you can still include it in your hierarchical flowchart, even though that verbal information is not part of the intellectual hierarchy. It is suggested that these skills be connected to the main hierarchical analysis using a connector like this:

Cluster analysis

If your goal falls in the domain of verbal information there will probably not be any specific sequence inherent in the information. In other words, it may not involve going from one step to the next. With verbal information you are not identifying a sequence of steps, but mainly you are just identifying the information that is needed to achieve your goal. In this case a cluster analysis is generally used. This involves identifying and grouping major categories of information that are implied by the goal, and then deciding how the information can be clustered together best.

Diagramming a cluster analysis can be achieved by using the hierarchical technique with the goal at the top and each major cluster as a subskill. Because your information is in clusters, and there is no explicit sequence, it is not considered a hierarchy.

Combination approach for attitudinal goals

Attitudinal goals also require a slightly different approach. The process generally involves asking the following two questions:

- What must learners do when exhibiting this attitude?

- Why should they exhibit this attitude?

First you should identify the behavior that you will look for to determine if the attitude is being demonstrated. What would people be doing if they were demonstrating that they were following the desired attitude? This will most likely be an intellectual skill or a motor skill. From there you should determine the goal steps and the accompanying subordinate skills just like you do for any other intellectual or psychomotor goal. You will then end up with a hierarchical analysis of skills that represent what learners will be doing if they choose to exhibit the desired attitude.

The second part involves explaining to a learner "why" they should make the choice to exhibit that attitude. The answer to this usually involves verbal information. For an attitudinal goal, it's not enough that you teach a learner how to do it; they have to choose to do it, and this is the information that will assist them in making that choice. The verbal information can be arranged in its own separate cluster analysis, or integrated into the overall hierarchical analysis.

On an instructional analysis flowchart, attitudinal goals are represented by attaching the attitudinal box to the intellectual or psychomotor skill that learners will choose to demonstrate. This is done using an "A" connector. From there you then list the necessary steps and skills necessary to achieve the desired skill. For the supporting verbal information (the "why"), you can either provide a separate cluster analysis, or integrate it into the hierarchical analysis by attaching each verbal "skill" in a box beside the psychomotor or intellectual skill that it supports. This is done using the triangular "V" connectors described earlier.

At the top of page 70, Dick, Carey and Carey give an example of what a diagram of an attitudinal goal might look like.

The techniques described in the preceding sections should allow you to ascertain and arrange the subordinate skills for each category of goal.

In the end, it is important to review your analysis several times to make sure you have properly identified all of the subordinate skills required for students to master your main instructional goal. Also, be on the lookout for skills that could be classified as "nice to know", but are not necessarily required for learners to learn the goal. It may be best to leave them out of the analysis.

Entry Behaviors

Once you have the subordinate skills identified, it's time to determine which of those skills you will treat as Entry Behaviors. Entry Behaviors are the skills and knowledge that the learners must know or be able to do before they begin the instruction. If you followed through with your subordinate skills analysis, the bottom of your hierarchy should contain very basic skills. If all of your goal steps are analyzed in this manner then you will have a complete list of all the skills required for a learner to reach your instructional goal. It is likely, though, that the learners already have many of these skills, so they will therefore not need to be included in the instruction you develop. These are the skills that you will assume that the learners have before they begin the new instruction.

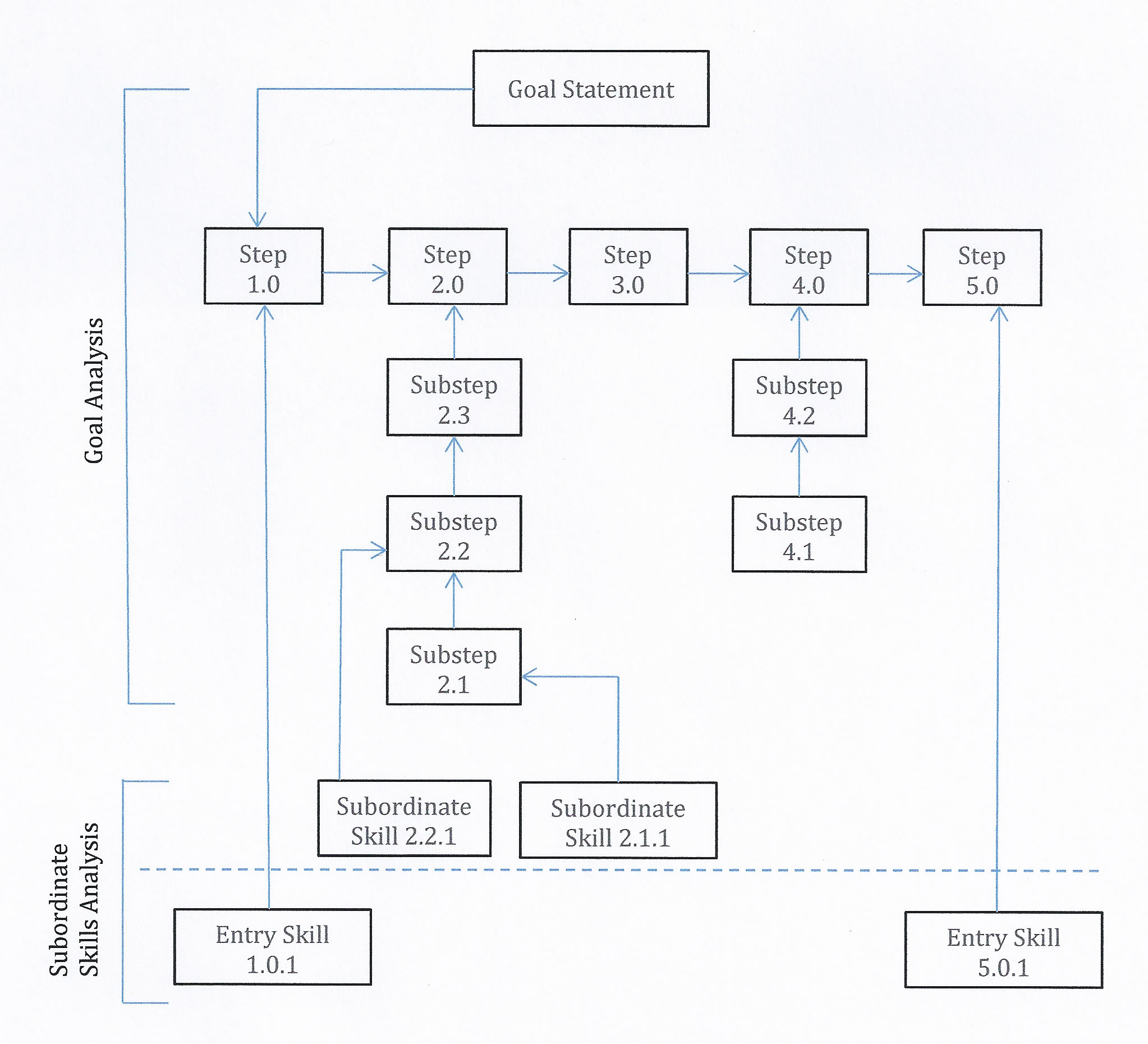

Entry behaviors can be identified in your diagram by examining your instructional analysis flowchart and identifying the skills that most learners will have already mastered. Once you have done this, draw a dotted line above the skills you identify as entry behaviors. What appears above that line is a listing of the skills and knowledge you will include in your instruction. Below that are the skills that learners should have previously learned; they will not be included in the instruction. The combination of both of these is all the skills they must have to perform the task that is essential for reaching the final goal.

Determining entry behaviors requires some assumption on the part of the designer. However, it is critical to the instructional analysis process as it helps the designer identify exactly what learners will already have to know or be able to do before they begin instruction. It also identifies what you, as the designer, will include in your instruction. If you "draw the line" too low then you will be teaching things that learners already know, thus wasting lots of development time and millions of dollars in costs (well, maybe not that much). Not to mention, your learners might be bored stiff. On the other hand, if you draw the line too high then your learners will not have the necessary prerequisite skills to be able to achieve your goal, and may just sit there with that "zoned-out" look. In this case your instructional materials would be ineffective. What all this means is that you should put some thought into who your learners are and what they might already know. If you are a teacher you may already be familiar with your learners. However, in other situations it may not be so easy, and you may want to seek out some more information before "drawing the line". If you have absolutely no knowledge of your intended learners at this point, then you might want to wait until after you have completed your Learner Analysis.

As an example, since your project in this course involves multimedia, you probably know that there will be certain computer skills your learners will have to have. It's up to you to determine which ones to treat as entry behaviors and which ones will need to be included in your instruction.

A Note on Numbering Conventions

The Dick, Carey, and Carey book provides many examples of instructional analysis diagrams. However, you may have noticed that the goal steps and subordinate skills in their examples seem to be numbered in an arbitrary fashion.

Because we think that it would be very helpful, we have created our own model, which you see below. In addition, we created a PDF version of it so that you can download it for easy reference when creating your own flowcharts.

Notice how the goal steps are numbered sequentially from left to right, while the substeps and subordinate skills are numbered from the bottom up. To summarize:

- The main steps are numbered from left to right using whole numbers with one decimal place (e.g. 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, etc.)

- Substeps for each step are numbered from botom to top. For example, the substeps for step one would be numbered 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, etc.

- Subordinate skills and entry skills are numbered in the order they are needed by adding a decimal place to the step or substep it supports. For example, if you identify three subordinate skills that are needed to perform step 2.0, they would be numbered 2.0.1, 2.0.2, and 2.0.3. If you identify three subordinate skills that are needed to perform substep 3.1, they would be numbered 3.1.1, 3.1.2, and 3.1.3.

- Verbal information is usually not numbered, but connected to the step or substep with a "V" in a triangle.

- Decisions are placed in a diamond. They usually result in a "Yes" or "No" response. The next step for each response is connected by an arrow that begins from one of the points of the diamond.

At the end of the subordinate skills analysis, you should have a listing of all the subordinate skills required to perform each of your main goal steps. As you can see above, your completed instructional analysis should then include the instructional goal, a list of the main steps required to accomplish that goal,the sub-steps required to accomplish the goal, the subordinate skills required to accomplish a step or sub-step, and the entry skills. This framework then becomes the foundation for all of the following steps in the instructional design process.